Glaucoma is a disease of the optic nerve, which transmits the images you see from the eye to the brain. The optic nerve is made up of many nerve fibers (like an electric cable with its numerous wires). Glaucoma damages nerve fibers, which can cause blind spots and vision loss. These nerve fibers are the axons of the ganglion cells within the retina. We are able to detect changes in both the ganglion cell layer as well as to the optic nerve that these axons form with modern day scanning devices in the office.

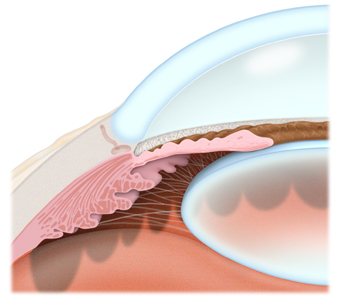

Glaucoma has to do with the pressure inside the eye, known as intraocular pressure (IOP). When the aqueous humor (a clear liquid that normally flows in and out of the eye) cannot drain properly, pressure builds up in the eye. When this pressure is too high for a given person’s optic nerve to withstand, the result is reflected by damage to the nerve’s form and function. With ongoing damage that is not treated, this leads to the patient noticing a loss in vision.

The most common form of glaucoma is primary or chronic open-angle glaucoma (COAG), in which the aqueous fluid is blocked from flowing back out of the eye at a normal rate through a tiny drainage system. Most people who develop primary open-angle glaucoma notice no symptoms until their vision is impaired.

The most common form of glaucoma is primary or chronic open-angle glaucoma (COAG), in which the aqueous fluid is blocked from flowing back out of the eye at a normal rate through a tiny drainage system. Most people who develop primary open-angle glaucoma notice no symptoms until their vision is impaired.

Ocular hypertension is often a forerunner to actual open-angle glaucoma. When ocular pressure is above normal, the risk of developing glaucoma increases. Several risk factors will affect whether you will develop glaucoma, including the level of IOP, family history, and corneal thickness. If your risk is high, your ophthalmologist (Eye M.D.) may recommend treatment to lower your IOP to prevent future damage.

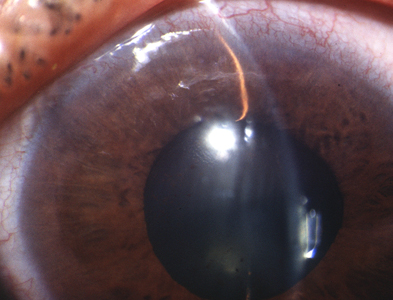

In angle-closure glaucoma (glaucoma secondary to ‘relative pupillary block), the peripheral iris (the colored part of the eye) may bow forward, as aqueous humor gets trapped behind it, and completely close off the drainage angle, abruptly blocking the flow of aqueous fluid and leading to increased IOP or optic nerve damage. In acute angle-closure glaucoma there is a sudden increase in IOP due to the build-up of aqueous fluid. This condition is considered an emergency because optic nerve damage and vision loss can occur within hours of the problem. Symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, seeing halos around lights, and eye pain. The definitive treatment requires a laser peripheral iridotomy, once medical means are used to begin to lower the pressure, so that the fluid no longer gets trapped behind the iris.

In angle-closure glaucoma (glaucoma secondary to ‘relative pupillary block), the peripheral iris (the colored part of the eye) may bow forward, as aqueous humor gets trapped behind it, and completely close off the drainage angle, abruptly blocking the flow of aqueous fluid and leading to increased IOP or optic nerve damage. In acute angle-closure glaucoma there is a sudden increase in IOP due to the build-up of aqueous fluid. This condition is considered an emergency because optic nerve damage and vision loss can occur within hours of the problem. Symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, seeing halos around lights, and eye pain. The definitive treatment requires a laser peripheral iridotomy, once medical means are used to begin to lower the pressure, so that the fluid no longer gets trapped behind the iris.

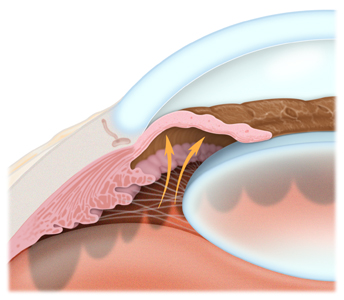

In plateau iris syndrome (primary angle closure glaucoma), rather than a relative block of aqueous humor behind the iris causing the angle to close, there is a unique anatomical change behind the peripheral iris. The ciliary body processes, the part of the eye that actually produces the aqueous humor that bathes the iris and lens, are rotated forward and push the peripheral iris forward, leaving the rest of the anterior chamber deep. If patients appear to have plateau iris on clinical examination, but their IOP spike is cured by a laser iridotomy, then they are said to have plateau iris configuration, as opposed to the true syndrome, which does not respond to a laser iridotomy. Patients with plateau iris syndrome, should their pressure fail to be well maintained, may benefit from laser iridoplasty/gonioplasty, cataract extraction if present, or endocyclophotocoagulation (ECP) in which laser is used to shrink the ciliary processes.

Even some people with “normal” IOP can experience vision loss from glaucoma. This condition is called normal-tension glaucoma. In this type of glaucoma, the optic nerve is damaged even though the IOP is considered normal. Normal-tension glaucoma is not well understood, but lowering IOP has been shown to slow progression of this form of glaucoma.

Childhood glaucoma, which starts in infancy, childhood, or adolescence, is rare. Like primary open-angle glaucoma, there are few, if any, symptoms in the early stage. Blindness can result if it is left untreated. Like most types of glaucoma, childhood glaucoma may run in families. Signs of this disease include:

- clouding of the cornea (the clear front part of the eye);

- tearing; and

- an enlarged eye.

Your ophthalmologist may tell you that you are at risk for glaucoma if you have one or more risk factors, including having an elevated IOP, a family history of glaucoma, certain optic nerve conditions, are of a particular ethnic background, or are of advanced age. Regular examinations with your ophthalmologist are important if you are at risk for this condition.

The goal of glaucoma treatment is to lower your eye pressure to prevent or slow further vision loss. Your ophthalmologist will recommend treatment if the risk of vision loss is high. Treatment often consists of eyedrops but can include laser treatment or surgery to create a new drain in the eye. Glaucoma is a chronic disease that can be controlled but not cured. Ongoing monitoring (every three to six months) is needed to watch for changes. Ask your ophthalmologist if you have any questions about glaucoma or your treatment.

The goal of glaucoma treatment is to lower your eye pressure to prevent or slow further vision loss. Your ophthalmologist will recommend treatment if the risk of vision loss is high. Treatment often consists of eyedrops but can include laser treatment or surgery to create a new drain in the eye. Glaucoma is a chronic disease that can be controlled but not cured. Ongoing monitoring (every three to six months) is needed to watch for changes. Ask your ophthalmologist if you have any questions about glaucoma or your treatment.

Glaucoma: eyedrops

View Video

(c) 2015, 2009 Robert M Schertzer, MD, MEd, FRCSC based on 2007 The American Academy of Ophthalmology